Morphic

Fields and Morphic Resonance

by Rupert Sheldrake

In

the hypothesis of formative causation, discussed in detail

in my books

A

New Science of Life and

The Presence of the Past, I propose that memory is inherent in nature. Most of the

so-called laws of nature

are more like habits.

My interest in evolutionary habits arose when I was

engaged in research in developmental biology,

and was reinforced by reading Charles Darwin, for whom the

habits

of organisms were of central importance. As Francis Huxley

has pointed out, Darwin’s most famous book could more

appropriately have been entitled The Origin of Habits.

Morphic Fields in Biology

Over the course of 15

years of research on plant development, I came to the

conclusion that for understanding the development of

plants, their morphogenesis, genes and gene products are

not enough. Morphogenesis also depends on organizing

fields. The same arguments apply to the development of

animals. Since the 1920s many developmental biologists

have proposed that biological organization depends on

fields, variously called biological fields, or

developmental fields, or positional fields, or

morphogenetic fields.

All cells come from other cells, and all cells inherit

fields of organization. Genes are part of this

organization. They play an essential role. But they do not

explain the organization itself. Why not?

Thanks to molecular biology, we know what genes do. They

enable organisms to make particular proteins. Other genes

are involved in the control of protein synthesis.

Identifiable genes are switched on and particular proteins

made at the beginning of new developmental processes. Some

of these developmental switch genes, like the Hox

genes in fruit flies, worms, fish and mammals, are very

similar. In evolutionary terms, they are highly conserved.

But switching on genes such as these cannot in itself

determine form, otherwise fruit flies would not look

different from us.

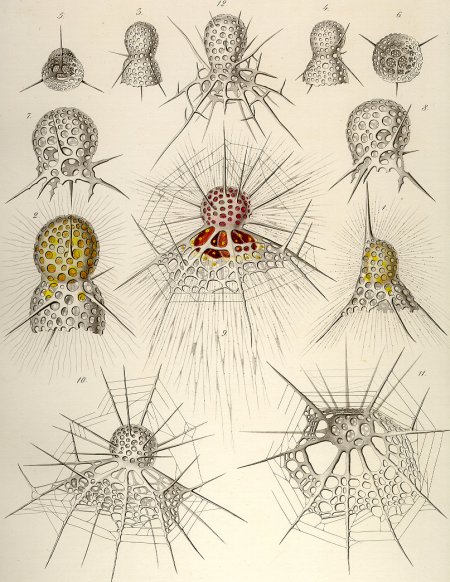

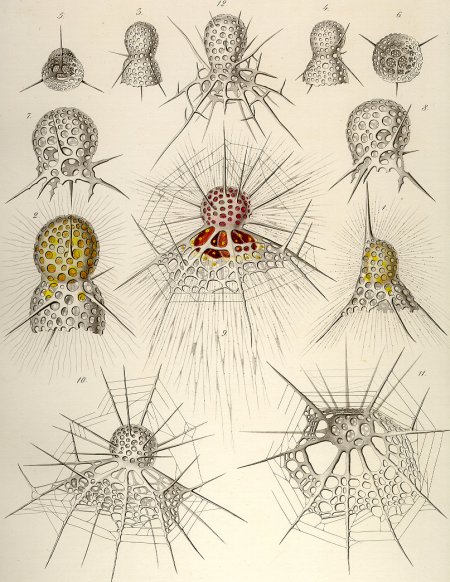

Many organisms live as free cells, including many yeasts,

bacteria and amoebas. Some form complex mineral skeletons,

as in diatoms and radiolarians, spectacularly pictured in

the nineteenth century by Ernst Haeckel. Just making the

right proteins at the right times cannot explain the

complex skeletons of such structures without many other

forces coming into play, including the organizing activity

of cell membranes and microtubules.

Ernst Haeckel Tafel 06

Most

developmental biologists accept the need for a holistic or integrative

conception of living organization. Otherwise biology will go on floundering,

even drowning, in oceans of data, as yet more genomes are sequenced, genes

are cloned and proteins are characterized.

I suggest that morphogenetic fields work by imposing patterns on otherwise

random or indeterminate patterns of activity. For example they cause

microtubules to crystallize in one part of the cell rather than another,

even though the subunits from which they are made are present throughout the

cell.

Morphogenetic fields are not fixed forever, but evolve. The fields of Afghan

hounds and poodles have become different from those of their common

ancestors, wolves. How are these fields inherited? I propose that that they

are transmitted from past members of the species through a kind of non-local

resonance, called morphic resonance.

The fields organizing the activity of the nervous system are likewise

inherited through morphic resonance, conveying a collective, instinctive

memory. Each individual both draws upon and contributes to the collective

memory of the species. This means that new patterns of behaviour can spread

more rapidly than would otherwise be possible. Foe example, if rats of a

particular breed learn a new trick in Harvard, then rats of that breed

should be able to learn the same trick faster all over the world, say in

Edinburgh and Melbourne. There is already evidence from laboratory

experiments (discussed in

A

New Science of Life)

that this actually happens.

The resonance of a brain with its own past states also helps to explain the

memories of individual animals and humans. There is no need for all memories

to be “stored” inside the brain.

Social groups are likewise organized by fields, as in schools of fish and

flocks of birds. Human societies have memories that are transmitted through

the culture of the group, and are most explicitly communicated through the

ritual re-enactment of a founding story or myth, as in the Jewish Passover

celebration, the Christian Holy Communion and the American thanksgiving

dinner, through which the past become present through a kind of resonance

with those who have performed the same rituals before.

The Memory of Nature

From the point of view of the hypothesis of morphic resonance, there is no

need to suppose that all the laws of nature sprang into being fully formed

at the moment of the Big Bang, like a kind of cosmic Napoleonic code, or

that they exist in a metaphysical realm beyond time and space.

Before the general acceptance of the Big Bang theory in the 1960s, eternal

laws seemed to make sense. The universe itself was thought to be eternal and

evolution was confined to the biological realm. But we now live in a

radically evolutionary universe.

If we want to stick to the idea of natural laws, we could say that as nature

itself evolves, the laws of nature also evolve, just as human laws evolve

over time. But then how would natural laws be remembered or enforced? The

law metaphor is embarrassingly anthropomorphic. Habits are less

human-centered. Many kinds of organisms have habits, but only humans have

laws. The habits of nature depend on non-local similarity reinforcement.

Through morphic resonance, the patterns of activity in self-organizing

systems are influenced by similar patterns in the past, giving each species

and each kind of self-organizing system a collective memory.

I believe that the natural selection of habits will play an essential part

in any integrated theory of evolution, including not just biological

evolution, but also physical, chemical, cosmic, social, mental and cultural

evolution.

Habits are subject to natural selection; and the more often they are

repeated, the more probable they become, other things being equal. Animals

inherit the successful habits of their species as instincts. We inherit

bodily, emotional, mental and cultural habits, including the habits of our

languages.

Fields of the Mind

Morphic fields underlie our mental activity and our perceptions, and lead to

a new theory of vision, as discussed in The Sense of Being Stared At.

The existence of these fields is experimentally testable through the sense

of being stared at itself. You can take part in a staring experiment

yourself through this website.

Click here

The morphic fields of social groups connect together members of the group

even when they are many miles apart, and provide channels of communication

through which organisms can stay in touch at a distance. They help provide

an explanation for telepathy. There is now good evidence that many species

of animals are telepathic, and telepathy seems to be a normal means of

animal communication, as discussed in my book

Dogs That Know When Their

Owners Are Coming Home. Telepathy is normal not paranormal, natural not

supernatural, and is also common between people, especially people who know

each other well.

In the modern world, the commonest kind of human telepathy occurs in

connection with telephone calls. More than 80% of the population say they

have though of someone for no apparent reason, who then called; or that they

have known who was calling before picking up the phone in a way that seems

telepathic. Controlled experiments on telephone telepathy have given

repeatable positive results that are highly significant statistically, as

summarized in

The Sense of Being Stared At, and described in detailed

technical papers. Telepathy also occurs in connection with emails, and

anyone who is interested can now test how telepathic they are in the online

telepathy test.

Click

here

The morphic fields of mental activity are not confined to the insides of our

heads. They extend far beyond our brain though intention and attention. We

are already familiar with the idea of fields extending beyond the material

objects in which they are rooted: for example magnetic fields extend beyond

the surfaces of magnets; the earth’s gravitational field extends far beyond

the surface of the earth, keeping the moon in its orbit; and the fields of a

cell phone stretch out far beyond the phone itself. Likewise the fields of

our minds extend far beyond our brains.

g

Rupert Sheldrake

is a

biologist and author of more than 75

scientific papers and

ten books. A former Research Fellow of the Royal Society, he studied

natural sciences at Cambridge University, where he was a Scholar of

Clare College, took a double first class honors degree and was

awarded the University Botany Prize. He then studied philosophy at

Harvard University, where he was a Frank Knox Fellow, before

returning to Cambridge, where he took a PhD in biochemistry. He was

a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge University, where he

read

more

Books by Rupert

Sheldrake:

Books by Rupert

Sheldrake:

A New Science of Life: The

Hypothesis of Formative Causation (1981)

The Presence of the Past: Morphic Resonance and the Habits of

Nature (1988)

The Rebirth of Nature: The Greening of Science and God (1992)

Seven Experiments that Could Change the World: A Do-It-Yourself

Guide to Revolutionary Science (1994)

-

Winner of the Book of the Year

Award from the British Institute for Social Inventions

Dogs that Know When Their Owners are Coming Home, and Other

Unexplained Powers of Animals (1999)

-

Winner of the Book of the Year

Award from the British Scientific and Medical Network

The Sense of Being Stared At, And Other Aspects of the Extended

Mind (2003)

Copyright © 2005 Entelechy: Mind & Culture. All

rights reserved