fall/winter, '06-07 , no. 8

Red Love

by Alice Andrews

[Editor's note: This is an earlier version of a story in Alice Andrews's novel Trine Erotic. ]

red

Oh, no, that’s not enoughI need a levitating love. — Caleb Matthews

That was the story Sullivan read on the computer; the story Karina wrote.

This is how it came to be written. This is how it came to be read:

There is a phenomenon known well to train riders called saccade. Without will, the central foveal area of the retinal field detects an object—a sacccadia—and then another. Karina watched this changing of focus from one point to another as she rode the number one train south. She watched as the passengers’ eyes danced involuntarily left, right, left, right—their eyes catching the large station numbers on the tiled walls—103, 96, 86, 79—as the subway sped out of the stations.

Between stops their eyes focused elsewhere. Karina imagined their lovers, their sadnesses, the dinners awaiting them. She was egalitarian about the images before her: the attractive ones caught her attention, but she scanned for the average, the flashless. The twenty-seven-year-old woman with three kids, no husband and two jobs, wanting love. A fifty-nine-year-old janitor with one son in jail, a daughter with HIV and who, just a week before his retirement is fired because someone accused him of stealing a computer at the school. Of course, he didn’t do it.

She watched mostly those unlike her, those who weren’t watching—the readers, the dozers, and her favorite, the unself-conscious subway primpers. Those who used the IRT for personal care were a strange lot. She had seen women put on too much makeup, saw a pretty Asian woman pluck tiny hairs from her face, saw a man brandish a pocket knife and use it to cut his fingernails, and once witnessed, horror of horrors, a man in a business suit floss his teeth.

Though her focus was mindful, there were times when even the fair Karina could not help herself. At a restaurant, say, with Sullivan, she might suddenly become uncomfortably aware that she was staring at a woman who sparkled, showed skin, or whose trip to the bathroom revealed a large, pantilined bottom through too tight pants. These sights stood out in the visual field despite others there who, if she thought about it, were more attractive and interesting—more aesthetically symapatico. She recognized, through catching herself watch these saccadias, these women with ample asses, low cut dresses and shine, that if this worked on her, it must work on men more so, on every level, and at all times. Whereas for her it was a visual atavism, an old deep reflex, she figured with Sully it was deeper but also closer to consciousness; it took up all his layers.

The world she created for the handsome man diagonal to her on the local was altogether different from the world he created for her. She imagined he was a Wall Street executive, Princeton raised and schooled who couldn’t commit to his longtime girlfriend and who was so tight with his money and affection he’d never be happy. It wasn’t exactly the world he created for her, saccadia, par excellence. He saw her in a black teddy with her leg up on a bed. No. His bed. He held her breasts, got her from behind and when he was done she conveniently had to go.

Karina had thought about getting off at seventy-second street to wait for an express but decided to stay on the local. When she got to forty-second street the express was across the tracks. She stood up and stood in the doorway of the car. She wondered if the express was about to pull out of the station. She couldn’t tell. She didn’t want to run across the platform only to have the express doors close on her, only to have to turn around and have the local doors close on her to be left without a ride. It had happened before. It wouldn’t happen again, she decided, and sat back down.

Saccade again. Eyes dancing back and forth, focus changing reflexively, automatically, without intention. And finally, fourteenth street. She stood up as Mr. Princeton gazed upon her, rehearsing his fantasy, and a bit sadly, exited the closing doors, leaving the folks with hard lives, and bounded up the stairs to twelfth street. On the corner of eighth avenue she rang the buzzer of an old warehouse. She peered into the conspicuous camera and was buzzed in to ISO headquarters.

These were strange, quiet times for the International Socialist Organization, indeed for all American socialists and communists. There was no Soviet Union. And the American youth, long cherished by the left, were, at best apathetic, if not conservative. Most of the radicals who managed to get through the apolitical me-decade eighties were too politically depressed by the mid-nineties, and many sympathetically abandoned the movement.

Karina supported and associated herself not only with ISO; she flirted with the SWL (Socialist Workers League), the ICP (International Communist Party), and the SP (Spartacus Party). Though there must have been dozens of small leftist groups, these were the ones Karina decided stood a chance of changing the world. And she was uniquely popular with them all. She was coveted like their golden girl, like she was Marilyn Monroe entertaining the troops. Karina was, for these old Marxists, their muse—their inspiration to fight the good fight; she got their sanguine juices flowing.

It wasn’t her intellect that moved them (perhaps some even wished she were less smart and critical), or her position on Yugoslavia, the former Soviet Union or her extensive knowledge of the '30s labor movement in America. It was that they wanted her, to possess her, to have her in their party—their poster girl. They wanted to see the beautiful Karina holding their sign saying, GM Workers Unite! Pick off the Scabs! Organize with Labor! For an Internationalist Workers Party! They wanted her because they knew people believed in beauty. Because they believed in beauty.

The truth is, the men in these organizations could not stop talking about her. They wanted to recruit her or seduce her, or both. (They knew about Sullivan but his existence didn’t seem to stop their fantasies.) And the women talked about her too—and not just the lesbians. In fact, the straight women did most of the talking—maybe so they wouldn’t feel bad when the men did or to show the men they didn’t care or weren’t intimidated. It was the alpha girls of the parties who had the hardest time with Karina. In the first place, she was at least ten if not fifteen years these girls senior—it hurt their young commie egos not to be able to keep the men’s attention with their infant flesh alone.

But it wasn’t simply Karina’s beauty that captured the fantasy lives of so many Bolsheviks in New York City. Karina was elusive. She would not be recruited and this made her desirability staggering. She was on every red’s mind all the time.

She figured, what’s the use of giving my life up to one marxist group if there’s no chance of class struggle? She vowed that she’d support them, go to meetings, fund-raisers, and demonstrations and if the time came and she was needed for important revolutionary work, she’d join. But it wasn’t her style to belong to just one group. Why the SWL and not the ISO? The factions and splinter groups were dizzying and imperfect: One group had great leadership but treated its women comrades miserably, another had great political positions but annoying and prickly party members.

How does the damn Democratic Party do it? Why can’t we just have one left party in this country? Our derision has led to our destruction, she had thought. She understood there were real political differences and why they were important, she just saw them as barriers to achieving what they all wanted: equality for blacks and other minorities, including women, the poor. Decent lives for everyone—not just in America but worldwide. To end human suffering.

Despite her beauty, Karina was not self-conscious the way other beautiful women were. One got the impression she didn’t know, though she had to, or if she knew, didn’t care. But she was self-conscious of her ancestry. She was part Scot, part First People. She had Native American blood—sort of injected into her. The First People’s of Onondaga, known as the People of the Hills, had stolen some of her recent ancestors in an act that left the family shattered and fragmented. Her great-great-great grandmother was kidnapped along with two of her children (a daughter, Sylvia, and son, William), leaving her great-great-great grandfather to raise Jacob, Samuel and Rebecca. Years later, after her great-great-great grandmother had died, Sylvia, along with her Indian family, visited the town from which she was stolen. She found her sister, Rebecca, married but childless. On the day of Sylvia’s return to her Indian village, she gave Rebecca a gift. Her name was Ewanni. She was Rebecca’s niece and would later be called Frances. And though she was beautiful—she looked like a Tibetan princess—many in the town talked about the “half-breed,” and though most understood why Rebecca kept her, no one could understand why Sylvia gave her.

Karina felt injustice in her blood. Within her she felt the injustice of her people, those who had been massacred and whose land had been taken from them, but also the injustice against her white family—who had also been taken. So it was that every wrong in the world, she felt, and this affected her glorious and healthy constitution.

At the ISO meeting, Karina sat on the old couch listening to the bearded brilliance of her comrades. They spoke every word for her. Every hard line, every polemic, was a seduction. But she didn’t feel right. It felt like a plant was growing in her throat, so she left the meeting early and watched saccade all the way home.

It was April but the city was brutally hot. Whatever virus Karina had, now seemed to cross the safe borders of her skin, infecting the world around her: Sullivan, the house, her relationships. For three days she would answer the phone with a fever. And in the evenings confess to Sullivan how she hurt Paul West, Louise Grosset or Harry Schafsma’s feelings and how rotten she felt about it. Sully tried to keep her from the phone. But Karina had a need to form and keep connections. She couldn’t let a virus stand in the way of maintaining relationships, after all. And so her actions reflected this social desire, but her words didn’t.

Maybe it was the fever, or free-floating anger—the kind that is native to us all. Or maybe it was specific and related to Sam, or Sullivan, or that C she got as an undergrad in her freshman seminar class with that right-wing professor. Or maybe it was what was just native to her. Whatever the cause, she hadn’t the strength or will of restraint. The virus had perforated that essential filter that gets most of us through the day—the social one. And hers was a sieve with large holes to begin with.

To her friend Louise she had been particularly cruel. About Gregory, her adopted son from Romania with the behavioral problem, she had said: “C’mon what do you expect? Do you really think Gregory can go from an orphanage where he probably got no more than twenty minutes of attention a day in miserable conditions, to an abusive foster family, back to the orphanage and then to you—a depressed, neurotic, forty-three-year-old single mom who can’t keep a job or finish her dissertation, without having problems? If he wasn’t fucked up by all that there’d really be something wrong with him.” She said this with some humor in her voice but Louise knew very well Karina meant every word and that she was probably right.

And then there was this conversation:

Lauren: I love him still. I’m in love with him.

Karina: Then why did you dump him, Lauren?

Lauren: You know why. Ultimately, he couldn’t get serious. Elizabeth thinks I was really strong to be able to do that.

Karina: You know what I think? In complete eros there is no Will to Power. In Will to Power there is no eros.

Lauren: What does that mean?

Karina: If you really loved him you wouldn’t break up with him just because he wouldn’t settle down. You’d keep hoping that he would. If you truly loved him, you’d be compelled to do anything to keep him. You’re not in love with him.

Lauren: Karina, let’s talk when you’re feeling better, Okay? I’m really upset about this now.

Karina was fascinated with this topic—more than she said, because she wasn’t well and because talking never afforded her the time to get at what she really wanted to, like her writing did. She knew people were fundamentally interested in their own story, the details of it—less in the meta-ness of it. But she wondered, What finally makes the less desired one, abandon ship? Is there a chemistry, a physics, a mathematics to it? Is it from strength or weakness? And why are there those who never leave, no matter what?

When she was better, she would think she was forgiven by her friends and colleagues because she was interesting and honest and vital—passionate about her students, about social change, and life. But what probably saved her was her beautifully round, sonorous laugh, mixed with an aesthetic ambrosia: her perfect milk skin, almond eyes and honey-wheat hair that made men want to take her home—because she actually lost Louise and almost Lauren. The lesson she would take home: don’t answer the phone when you’re sick. But she’d do it again.

It seemed Karina’s abundance of energy was reserved only for lecturing friends and Sully during her sickness. Anything else was too much: cleaning dirty, three-day-old dishes—some having never made it to the sink, including her paternal grandmother’s eighteenth century English ‘peony’ plates, which had glued to them, perhaps forever, the Chinese food she had eaten before she got sick, picking up “papers”—those damn papers that she often hounded Sullivan about—memos, receipts, magazines, messages, bills, empty envelopes, his work—everywhere.

Sullivan worshipped her. Sure they had been fighting a lot but who didn’t fight? He was tense working on his doctoral degree—the academic politics were more than he had bargained for even with his progressive milieu. He had been with pretty women all his life but never a woman whose beauty made men stutter or silent. She had had that kind of affect on him when they first met. He was looking for a roommate. He listed his share with Columbia’s off-campus housing office and put signs on the street lamps and bus shelters along Broadway. He got a dozen and a half calls and from those calls met about eight of them. When Karina walked into the apartment Sully was stunned. What was she doing looking for a roommate? Why hadn’t she been swept up by some exceedingly wealthy businessman or Hollywood executive? Couldn’t someone like this be a model or an actress? She’s an English professor and wants to share my place and sleep in the living room?

His friends told him it was a terrible idea to live with a woman who made him weak and who he said he thought he might already love. And he had only several months ago broken up with Abby. He wasn’t thinking straight, his friends told him. But he offered the living room to her and in two months they were both in the bedroom.

Sure, things have slowed down in bed, he was thinking to himself and the fighting had steadily increased but he knew that was fairly typical when you lived with someone. He expected it. He had no doubts about their relationship—he figured they’d marry after his Ph.D. in history and have kids. She’d be in her late thirties—she’d fit in perfectly with the other mothers he saw strolling babies on Broadway. But maybe Karina didn’t feel this way. Every fight took away something for her—maybe feeling. Maybe she doesn’t feel what I feel, Sully was starting to think.

Sully was no longer helping out. His energies, although boundless, were confined to one area or project in his life. In the heady days just a couple of years back with Karina, everything else fell to the side. But now his project was renovating a three-bedroom apartment on West End Avenue to which he devoted all his energies, and this somehow translated to a light touch in domestic areas.

Karina was beginning to fear that it was Sully’s perfect, beautiful rent-controlled, pre-war, one-bedroom on Riverside Drive that kept them together when it seemed nothing else would. The apartment’s lease had been his uncle’s—a barrel of a man and Johnsonian Professor of History at Columbia. Uncle Sullivan and Sully shared the same name—Sullivan T. McCoy—which enabled Sully to take over the place when Uncle Sullivan left Morningside Heights for a better life and a better deal at Harvard.

Karina’s non-tenured teaching salary at City College was decent but not enough for her to get a studio that was half as nice as Sully’s eight-hundred-square-foot spread. (Comparable one-bedrooms would cost more than double what they paid for the place.) And Karina realized that although Sully could arguably find another roommate, he or she would have to sleep in the living room. And since he had now lived with a living room without someone’s life in it (bed, dresser, body, personal affects) for two years, Karina knew he’d prefer living with her and one bed in disharmony, than with the alternative.

One of their problems, it seemed to Karina, was that for many months, their fighting had degenerated into passionless banter and worse: right in the middle of an argument, either Karina or Sullivan would ask to end it. To her, this was contrary to universal laws of arguments, which boil and boil rapidly, effortlessly, and hard—until something happens—someone runs out of the apartment and the other chases; someone cries and the other consoles; someone apologizes and the other accepts; someone, in this case, Sully, bangs his fist on a door and it busts open—not the door; or the fight slows down from hours and hours of exhaustion until there’s a stalemate and both forgive and forget. But asking in the heat of an argument for a cease fire? It was an unnatural conclusion, a forced consequence that went against her literary and philosophical sensibilities. But mostly it went against her passionate and stubborn nature, and it bothered her deeply.

But she was as guilty as Sullivan. She also had become enervated by the arguments and could no longer keep them going. Better to end them sooner and save some energy for grading papers, she’d think. She feared it meant they no longer thought each other was worth the effort, but she hoped it was because they were working too hard—and because they had been together just over the two year mark where evolutionary psychologists say that the love chemicals peter off and the commitment molecules set in. Perhaps this new style of argumentation was good, she told herself. It was natural. It followed the logic of the sexes throughout evolution. The hot emotions of love and passion produce intense arguing, the cool feelings of respect and commitment urge you to stop: Get on with feeding babies, making weapons, hunting, gathering, bonding with other tribes—grading papers.

Karina had been feeling the mind-body dialectic problem for a while. Not really the philosophical one, so much as the one which relates to her and men. She felt it was only her outward beauty that Sully was magnetized to. But he didn’t seem to get her. He seemed to hate her intensity and passion. He wasn’t that interested in her ideas, either. It felt like a waste. And she sort of didn’t feel loved. Most any man could love her face, her body, but the man who loved the fire in her, the burst of memes in her, the artist in her…

Sullivan was a good man and she valued that. But she hated herself for not valuing it enough. It’s like both had an abundance of qualities which the other ultimately wasn’t turned on by. And yet, the contradiction was, they both needed those qualities.

She imagined a conversation with her colleague, Paul West, also an English professor at City College:

“Do you know Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy?” she asks.

“Sure,” he says.

“I’ve got this student who used it in his paper on

Sophocles. He didn’t get it right but it’s interesting—”

She’s cut off in her own fantasy.

“What is it...Dionysus versus Appolinian?”

“Yes—the Dionysian.”

“Yes, right,” he says, “Dionysian: irrational, overflowing, intoxicated, voluptuous, destructive. The Appolinian: rational, imagistic, and creative. In art, the Dionysian is music, the Appolonian, paintings, drawings…Right?”

“Yes. And within the classification of Dionysian art—music—there is a continuum of the Dionysian and Appolonian. Which do you think I’m more like?” she asks.

“Probably both. That’s usually the answer to questions of dualism, right?” he says.

“Tell me more. . .”

“Well, on the outside you are definitely Dionysian. It’s your job to deconstruct—language—and papers.”

“Deconstructing language makes me Dionysian?” she says.

Like a dream where the players change in the middle of the action in a kind of morphing, she now imagined the conversation was taking place with Sullivan:

“No, Kar. I was just kidding. But really, you’re about breaking down walls, right?—politically and artistically—even if you’re not always successful. And your drinking—”

“Wait, wait, wait—I asked a philosophical question here and you’re on to me about drinking!”

She was kidding, she really wasn’t feeling defensive, but this was typically lost on Sullivan, even in her daydream.

“I’m not onto you. Okay, on the inside though, of this teeming sexual, hot, voluptuous, irrational woman there is an Appolinian impulse—a need to create and to build and to give life and meaning to things. Your stories. And you want children. Some revolutionary!”

“And you’re both too I now see: look what you do—construction, you build stuff. And history (Sully was a carpenter by trade but a Ph. D. candidate at Columbia by fate—all the men in his family and one aunt were historians—a few were marxists) it’s analytical, ordered, rational, and you are a costructivist aren’t you?”

“Touché.”

“But inside you know you have to deconstruct to build, and I know what pleasure you get in ripping stuff down. And once you were talking about Spain and you said in your most revolutionary and innocent way: ‘Sometimes you need a revolution to create a better world,’ and I told you then—surprise, surprise—that you were right.”

“But revolution is not my impulse. Creating a better world is and it has been necessary for—”

“Okay, okay. Let’s not get into this. We’re both Appolinian and Dionysian.”

It was her musing, so she had the last word.

It’s frightening, but Karina truly had daydreams like this. It scared her too. She had read somewhere that men have sexual fantasies nine times a minute. If only I were a man, she thought. Her fantasies were socio-logos-centered—in a word, Appolinian. Her fantasy life was limited to imagined conversations (political, literary, philosophical) imagining people’s lives and her own acts of heroism. They were a precursor to her stories. If only she could imagine Paul or Harry in bed, or that sexy, new guy in the ICP who looked like Ed Burns—she’d be a lot happier, she knew. But the Dionysian wasn’t flowing, her guilt saw to that.

Karina was starting to feel better. She was slowed down and well enough in this twilight between illness and recovery that she was able to take long, hot baths with lavender and chamomile. She could fantasize. And she could write.

To piece stories together until she was all right in her mind and body.

She was well enough to read an article in the Sunday Times Magazine called, “Save Sigmund Freud: What We Can Still Learn from a Discredited, Scientifically Challenged Misogynist.” She read:

Because we both wish and oppose our own desires, our inner lives are in a constant state of civil war. What Freud taught us to do was to recognize the signs of that war and to see when it was reaching destructive imbalance. He let us know how we’re likely to behave when desire slips loose from its reigns, but he also told us the price of too much prohibition. When the inner censor grows too strong, prohibits too much, the result is listlessness, depression, despondency. In extreme cases we reach acedia, the hatred of life that takes one to suicide. The death of desire is the death of the individual.

It was impossible for Karina to read the word suicide and not think of Sam. She lay back in her bed and thought of the last time she saw him and about how fooled he had had everyone. She hadn’t known—no one knew—the kind of pain he was in or why. Sam playing football. Sam at the prom with the girls with big hair. Sam, the eternal yes-sayer, or so she had thought. It had been fourteen years since Sam had killed himself up at SUNY Oswego. A premeditated drug overdose. He left a three page letter to his friends and family. Mostly the letter dealt with his possessions and where and to whom they should go. Their brother Joe got his prized comic book collection; Karina got his journals, of which there were many. She tried to read them when she came home for the funeral her senior year at Stonybrook. But Karina and Sam had been terribly close. And when she picked up those notebooks she felt the life in them. She felt his energy pass into her fingertips, up her arms, and down her spine. The intensity of her feelings, the crying and wailing, surpassed anything she had ever witnessed on television, on film or on stage. Art and culture betrayed her. It didn’t prepare her, it didn’t reflect her torment. And it was because her pain seemed so outside the normative values and understanding of culture that she worried about the depth of her feeling. And she was told often enough she wasn’t normal. It’s not normal to be raw four years after the death of a brother, someone once told her, blindly.

At first, Karina put the inherited journals in his room under his bed. He had kept them in his closet. And sometimes when she was home in Oswego at Christmas she would try to read them with her mother, but they both feared the notebooks would interrupt what little healing had begun. There was never a good time to read the Logos of your dead brother. One year she brought the journals back to the city with her, and stored them from apartment to apartment.

It had taken her almost five years for her to be able to go into the room Sam shared with Joe, their older brother, for any length of time. And when she was finally able to go in she’d sit in the middle of the floor holding something—a high school biology book that he never returned, a picture of one of the many girls he had dated. And then she’d go into their small bathroom and open the old medicine cabinet. She’d look at all the soaps, medicines, and general toiletries and wonder why her mother hadn’t thrown them all away. She’d take down his shaving cream and squeeze foam out as big, fat tears rolled down her thinning cheeks. How can this still be here and not you? she’d say aloud, gazing past the worn, milky mirror, through her reflection, past sensory impressions, to the other side of the looking glass, hoping to find him. Many, many years later, she’d perform her ritual at the medicine cabinet, and think, old smelly shaving cream, way past its expiration, it wasn’t supposed to last longer than Sam, it doesn’t have a right to last this long. She hated Gillette.

It was in Sully’s apartment, in an old milk crate, at the back of the hall closet, that the answer or answers to Sam’s desperate act might finally be found. She felt ready. She wasn’t raw. She felt healed on the top layers. And she was smart enough to be prepared not to find answers. Now, during this strange free-time, between bedridden and work, which she equated with the time spent at airports, she’d finally read them. It was Sully’s earlier rummaging getting the air conditioner in the front closet which managed to bring the crate in front of her when she opened the closet door. She was eerily amused. If she ever fictionalized this, this moment would have to be cut. Too often life gave her perfect, serendipitous occurrences that were too hokey, too unbelievable for fiction. Her life wasn’t stranger than fiction it was more fictiony than fiction—at least modern fiction.

After reading through most of them, Karina was inspired—compelled to write.

She wrote:

The artist must have something to say, for mastery over form is not his goal but rather the adapting of form to its inner meaning.

What gaps do I leave? How much to give to the reader? When is it too much? Not enough? It’s like seduction. Too much—it’s obscene. Too little—not enticing. How to give enough flesh so they want more? And what do I want to do? I want to:

Draw the reader in—like a friend sitting down at a coffee shop eager to hear the news of a new romance—or affair.

Heal the reader or give reader an a-ha, make reader laugh, or think, or remember—give pleasure.

Use details and description sparingly, with meaning and purpose.

Eschew dead, cliché phrases or metaphors. And if not, use them correctly (e.g. begs the question). Conversely, don't fear universals, like love, because they appear unliterary.

Offer depth and layers and resonance for excavators and detectives.

Be clear.

Be unpretentious and honest. Postmodern jargon should neither hide a weakness to explain or describe, nor cover up what is nonsense, weak, empty.

Have as many people read it as possible.

Be happy if it’s only published in Splinters—or nowhere.

Write things people are afraid to say so that they can say them.

Because that’s one of art’s missions. It pushes us. It reveals. It pries us open little by little, exposing us, in a comfort zone. It’s about normative values. And power, of course. If you rule art, you rule the world. Forget about the means of production. Art changes the strategy of reproduction. We are the product of art. Our minds, our bodies. What cultural products are valued? Rejected? What survives? Who survives? Art throughout history—the progression and unfolding of it.

And then she wrote "soft kill."

Days later, she and Sully sat down to eat Indian take-out in front of Entertainment Tonight after his very long, hot day of ripping out molding and skim coating. Karina was feeling better and was full of energy and spice. She wanted to engage him in ideas, half-thought out ones, and Sully wanted a beer and a game.

“There are three kinds of people in the world,” Karina said.

“Yeah? Do you know what channel MSG is on?”

“Twenty-nine or twenty-three. Do you want to hear my three kinds of people idea?”

“I’d rather watch the Yankees,” Sully said wryly, thinking his audience would not take offense. He dialed around for a while and returned to Entertainment Tonight, defeated and miserable.

“A King Fisher would really be good right now but I’d settle for anything.”

Karina went into the kitchen and grabbed a Rolling Rock for him.

“Here, Sul. Okay, so the idea is that there are three kinds of people: readers, writers and livers.”

“Livers?” Sullivan said disgusted.

“Yes, livers—hold the onions. As in those who live—it is a word. I know it’s not beautiful. I thought of “lovers of life” instead—a sort of reference to Plato and it sounds better, but it messes up the symmetry with ‘writers’ and ‘readers.’ Anyway, I’m sticking with livers. You may think of it as the ‘lovers of life’ if you want.”

“Alright, alright, you’re going to lose me if you, hey, I found a game,” he said, holding the remote in the air like it was a magic wand.

“Okay! Most people in the world are readers—passive, taking the world in, experiencing other people’s experience or imagined experiences—watching TV is “reading.” The writers (and one needn’t write to fit into this category—it’s more like a sensibility)—”

“Oh no?” Sully said ironically but with his interest piqued a bit at this seeming contradiction.

“...are observers, reflective, they talk about experience, write about it, respond to it. The livers, are busy living so they’re not writing or reflecting because they’re caught up in the moment of their experience—living it. We’re all probably all three at different points in our lives, at different times of the day. Observing, acting, reflecting.”

“Okay, so I’m a reader obviously. And you? You’re a liver, right?”

“I’m all three, but I guess I’m mostly a writer, unhappy being a reader, wishing I were a liver. I’m comfortable observing, reflecting, learning, responding—not as comfortable being passive, but I guess I want to live more. I want to live fully and feel fully. To be truly alive.”

“You lost me there, Kar. That’s the way I think of you, can’t think of anyone more like that than you.”

“I’m glad, at least I put on a good show for all you readers.” Karina laughed, knowing she didn't have much longer before Sully lost interest.... She thought to herself, I don’t want to think when I’m doing. I want to lose myself. In the moment. To be pure—without self-consciousness, without thought.

"You know, I think somehow those three modes of being must be similar to the three gunas—in Indian philosophy," she said.

"What's a guna? Sounds like something you put on nan bread."

"I suppose you could. But, gunas are the three modes of nature—sattva—goodness, rajas—passion, and tamas—dullness."

"Mmm, I'd like some rajas and maybe just a little sattva—hold the tamas."

"I bet you would like a little rajas."

Can you pass the raita?" he said.

"Sure...here...but anyway, the three gunas are—

“Wait, wait, shhh for a second, that’s Tony Rivera—he hasn’t struck out once this year and the pitcher—Gary Rodd—is the best there—shit, it’s out—it’s out of the park!! Hooohoeow. Okay, what was that, Kar?”

“That’s okay,” she said, "I was just going to go on about gunas. You'd rather hear about aesthemiotics, wouldn't you?

“I don't know. I don't know what it is...Aesthetics and semiotics?”

“Very good.”

“What is it?”

“It’s the aesthetic interpretation of signs and codes. The study of the phenomenon of beauty becoming its opposite. And the reverse—the ugly becoming beautiful. When an attractive signal becomes "too loud," "grotesque," how the signal loses its power from "trying" too hard, how it becomes ugly."

“You lost me,” he said. To be fair, he was trying to watch a game.

“Okay, think of anorexia. In anorexia, women's bodies are symbolic of the Nietzschean "ascetic ideal," which is fundamentally anti-grotesque. By demonstrating the ascetic ideal, the lack of excess and spectacle, she reaffirms excess—she becomes grotesque.”

“You gotta give me something more than that postmodern crap!”

“OK, Monsieur Foucault,” she said. Sully had an annoying habit of acting disdainful of academia, when in fact, he was seriously in the muck of it. Maybe that’s why.

“Alright...a better example is the “grunge” look. When we were in school, a decade before it was called “grunge” it was a code, remember? For an abundance of resources and creative impulses—only a rich college kid or a kid with artistic talents could “afford” to wear the “sign” of torn leather and low, dirty jeans. There was beauty in the old and worn. It represented an emphasis on the interior. It was a reaction to the status symbol fashion—an exaltation of the poor. It was sort of Jesus-like. Spiritual. There’s beauty in the strength of someone who doesn’t care about her image. Behind the five dollar vintage dress with holes lies—we imagine—an inner beauty or talent or resource or strength. But with time, the sign becomes saturated. The look loses its meaning as it becomes popular, and counter reactions appear—a new code or signal.”

Then she asked him to read her story. She was clearly pushing it.

“Forget it, Karina! Just about every time you’ve made me read one of your stories, I’ve ended up downtown all night with Gary, plastered, or you’ve gone down to Helen and Sasha’s, or we’ve talked about your moving out. I don’t want you to move. Anyway, you like it here too much. You like the views—you even sometimes like me.”

“Humph!” Karina said. Sullivan grabbed the Sports section of the Times and escaped to the bathroom. She followed him and despite herself stood outside the door unrelenting.

“Karina—I’m busy here?!” Sullivan said, now angry. She opened the door part way.

“I thought you might find it interesting, I just want a little feedback, Sul.” He threw down the paper, “Jesus Christ, Karina, you should leave me alone.” She went back to ET and he joined her one segment on Johnny Depp later. Restraint was not her strong suit.

“If you’re concerned it’ll bring up issues—” Karina continued to hound Sullivan who now was concentrating undeliberately and unconsciously on a commercial with a lot of women’s tan flesh. It was that degrading, campy beer commercial that poked fun at sexist beer commercials while all the while owning Sullivan’s occipital lobe. On a moral and practical level, this irritated Karina to the point of frustration. But in the abstract, Karina enjoyed this about him. He was a handsome, hard working, enlightened academic who appreciated tits and ass as much as her brother Joe—an unenlightened UPS driver, in Onondaga, New York, or her Uncle Dick, and her own father, both fishermen did. Sullivan wasn’t working class, but at least he shared some of their sensibilities. “Sully!” Karina jabbed.

“Sorry—what?” Karina could see she was beat.

Days later, Karina was better and back teaching. Having reread her story, she realized Sullivan was smart not to want to read it.

But Sully was in their bedroom, at the desk with the computer on. He had a paper to write and was looking for distraction. Anything was better than: The Era of NEP: 1921-1928:

How does NEP bring ideological consistency to the revolution that was prematurely staged in November 1917?

He started by looking around at all the pretty things Karina had about.

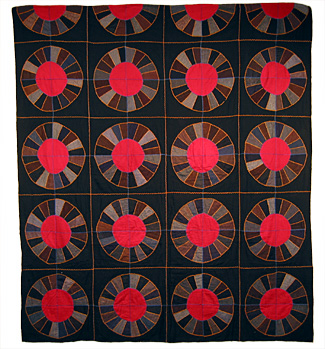

He gazed at the simple African-American quilt hanging on the wall; it was a Log Cabin quilt: red, orange, black, purple, brown, turquoise and yellow, with a black backing.

Karina loved that quilt. She had been turned on to quilts after reading Sue Bender's Plain and Simple: A Woman's Journey to the Amish. She became particularly interested in African-American quilts and often enough incorporated some piece of information about them into one of her classes. During sections on the Reconstruction period, she would explain how quilts were used as maps to freedom for members of the Underground Railroad. She'd bring in her own quilt and large picture books on African-American quilts to show them. The North star, crossroads, log cabin...all these patterns within the quilt represented a message, a signal. Karina loved this. Art as code and signal. Art as savior, as rescuer. She never felt badly that most of her students weren't that interested because it wasn't "cool." She knew they were busy weaving their own lives, looking for their own codes and signals—maps to freedom. But she always hoped that despite their seeming apathy, that the quilts would reach a place beyond "cool" and have some meaning for them.

Sullivan tried to remember what she had told him about these quilts. He remembered there was something about the black cloth on the back, but forgot what: That Log Cabin quilts with black cloth were hung to mark a safehouse of refuge. And there was something about the patterns in the quilts and evil spirits. But he couldn't remember that either. What she had told him was that aside from the messages within the quilt, there was also significance in the patterns—particularly the breaks and changes in the patterns. Many African tribes believed that evil traveled in straight lines—so, the break or change was meant to confuse the evil spirits and slow them down. Wearing or having or creating this art, symbolized a kind of rebirth, a kind of power.

He gazed at the beautiful antique etching of three women dressed in flowing gowns in the style of Tadema and Burne-Jones propped up on the desk. He studied it carefully. He had never noticed it before. One woman was at a spinning wheel. Another woman’s hands were outstretched. The third woman held a pair of shears. They just looked like three beautiful women to him. They looked like Karina. But they were the three fates: Clotho, the spinner of the thread of life; Lachesis, the disposer of lots, assigning each person's destiny; and Atropos, the one who finally cuts the thread. He couldn’t have known that. Actually, Karina hadn’t known either. It was just something she found at an antique shop once.

Then his eyes went back to the computer. NEP. NEP. Fuck NEP! That “soft kill” icon on the desktop made him curious. He double-clicked on it and began reading about the memes, Jonathan’ lack of focus on Sarah and her baby theories ...

After he read it, he reread the last line: “And though they both knew it was his kind of love they soon forgot.”

Sully closed the document and sat there for a while looking at the blue screen and out at the river.

Karina came home and walked into the bedroom.

“I read ‘soft kill’,” Sully said. And then a bit sadly, “It made me think about things...You’re going to leave, aren’t you?”

And Karina said, with the lightness of a finch’s wings, “Oh, Sullivan, it’s just a story.” <

A

lice Andrews (with philosophy and psychology degrees from Columbia University) teachespsychology with an evolutionary lens at the State University of New York at New Paltz, where she is helping to implement an Evolutionary Studies program modeled on David Sloan Wilson's EvoS program at SUNY Binghamton . She is an editor and writer (books and magazines), and was the associate editor of Chronogram from 2000-2002. She is also the author ofTrine Erotic , a novel that's been used in various college courses nationwide because of its loration of evolutionary psychology. Alice is currently working on a book (based on her essay with the same title, published at Metanexus) called An Evolutionary Mind (to be published as part of Imprint Academic's series: "Societas: Essays in Political and Cultural Criticism"), and plans to begin writing another novel soon.. exp